As a volunteer, Paul ‘Woody’ Woodward prefers to do as little as possible.

“I want to be bored,” says Woody. “Boring is good.”

That’s because when Woody and his 84 fellow mountaineers of the elite Alpine Rescue Team (ART) have something to do it usually means that somebody’s in a peck of trouble. ART performed 145 rescues last year, a new record that’s on track to be broken this year, and broken again the year after that.

“As the state’s population goes up, so does the number of people using the back country,” explains Woody, a fifth-generation Coloradan and 29-year ART veteran. “It’s a trend happening statewide.”

Even so, clocking in on the morning of June 13 he had reasonable hopes for a tedious shift. “Tuesdays are usually pretty quiet.” He stopped hoping shortly before noon.

“A 22-year old male had a bad allergic reaction on Mount Bierstadt.”

Woody’s one of ART’s 15 mission coordinators, each one on call two days per month. When somebody gets cross-ways with the great outdoors anywhere in Clear Creek, Gilpin and Jefferson counties, it’s the coordinator’s job to assemble a crew and direct the rescue. An able 19 team members answered Clear Creek’s call to Beirstadt and made tracks for the mountain. As good luck would have it, the problem resolved itself while the team was in transit.

“Right as we got there he hiked out,” Woody shrugs. “So we turned around and came back.”

It happens that way sometimes, and that’s just fine with ART. A second call at 2:30, however, wouldn’t be answered so easily.

“A 31-year-old male fell while rock climbing in Golden Gate Canyon.”

Extracting the unfortunate fellow required that a 22-member team first reach his isolated location and secure him to a litter, and then haul him 400 feet straight up to the ridgeline and painstakingly lower him 800 vertical feet down the other side.

“It’s a lot of work,” Woody laughs.

The four-and-a-half hour operation was a solid day’s duty by any standard, and it was about to look like a milk run.

“Now it’s 7 o’clock and we get the big call. A 16-year-old male is missing, last seen at the summit of Mount Evans.”

“Now it’s 7 o’clock and we get the big call. A 16-year-old male is missing, last seen at the summit of Mount Evans.”

The missing teen was from Atlanta, the guest of a Rocky Mountain summer camp, and on that sunny Tuesday a family friend had driven him to the top of Mount Evans to suck up an eyeful of Colorado’s high-altitude grandeur. The young man hiked the short trail from the parking area to the 14,265-foot crest, posed for a few smiling snaps, and things had gone downhill from there.

“Instead of hiking back down the trail to the car, he made a fateful decision,” Woody says. “He didn’t know the terrain, wasn’t familiar with the area, but decided he could walk down to Summit Lake on his own. He told the family friend he’d meet her at Summit Lake and waved goodbye.”

It takes time to organize a rescue. Team members converge on ART’s headquarters in El Rancho from all parts of the Denver metropolitan area, from there heading west into some of the Centennial State’s least-welcoming terrain. It was well after 8 p.m. before rescuers had firmly staged at Summit Lake, and the odds of swiftly locating a boy alone in that harsh wilderness were falling as fast as the westering sun.

On the likelihood that the teenager’s trail led north along the rocky West Ridge connecting Mount Evans to neighboring 13,842-foot Mount Spalding , teams deployed to both peaks while spotters set up at Summit Lake made use of the day’s last, thin light to scan its length from below. Between the two summits stretched a vast bowl, its plunging sides a dangerous jumble of blasted rock and loose scree. The missing boy could have been anywhere within that impenetrable landscape. Or nowhere.

On the likelihood that the teenager’s trail led north along the rocky West Ridge connecting Mount Evans to neighboring 13,842-foot Mount Spalding , teams deployed to both peaks while spotters set up at Summit Lake made use of the day’s last, thin light to scan its length from below. Between the two summits stretched a vast bowl, its plunging sides a dangerous jumble of blasted rock and loose scree. The missing boy could have been anywhere within that impenetrable landscape. Or nowhere.

If he’d had a smart phone, his ordeal might have been over in hours. Alpine Rescue could have located him by GPS, or instructed him to turn on his flashlight app and zeroed in for a quick extraction. “We were looking for the only teenager in America without a cell phone.”

The Evans team was met at the top by sustained 60 mph winds, It may have been Spring on the calendar, but it was still winter on top of the Rockies.

The Evans team was met at the top by sustained 60 mph winds, It may have been Spring on the calendar, but it was still winter on top of the Rockies.

“It was 80 degrees in Denver that afternoon,” Woody recalls. “With wind chill, we figured it was close to zero on the ridge. The kid was wearing blue jeans and a hoodie,”

As the Evans team probed west and then north along the ridgeline, their counterparts laboriously worked their way up the steep Mount Spalding trail. They’d nearly reached the summit when they were stopped in their tracks by thin scraps of a cry for help, desperate shouts torn to shreds in the teeth of the gale. Listening intently, the Spalding crew’s best guess put the voice’s owner somewhere far below near the boggy mouth of the creek that feeds Summit Lake.

Immediately, and in full dark, they started descending a sheer and trackless tangle of boulders and scale, bottoming out at about midnight to find the narrow valley floor deserted. They called out, and were answered from somewhere directly above them. Without hesitation the Spalding team started climbing, clawing its way up slope no less forbidding than the one they’d just come down. For three perilous hours the men fought their way upwards through 150 stories of precarious talus and treacherous snow before finally running straight up against a sheer wall of stone. It was 3 a.m., and they were just 200 feet below the voice in the darkness.

“They simply didn’t have the equipment they needed to continue,” Woody says. “They spent the rest of the night right there, yelling up at the young man every five minutes, trying to keep him calm and reassured.”

“They simply didn’t have the equipment they needed to continue,” Woody says. “They spent the rest of the night right there, yelling up at the young man every five minutes, trying to keep him calm and reassured.”

If Woody now knew the lost teen’s location, he also knew he had a team exposed and at risk on a dangerous slope, and he knew that getting everybody out safely wasn’t going to be easy. He called for reinforcements from Boulder’s crack Rocky Mountain Rescue Group (RMRG), which sent over a team specifically outfitted for the tough jobs ahead.

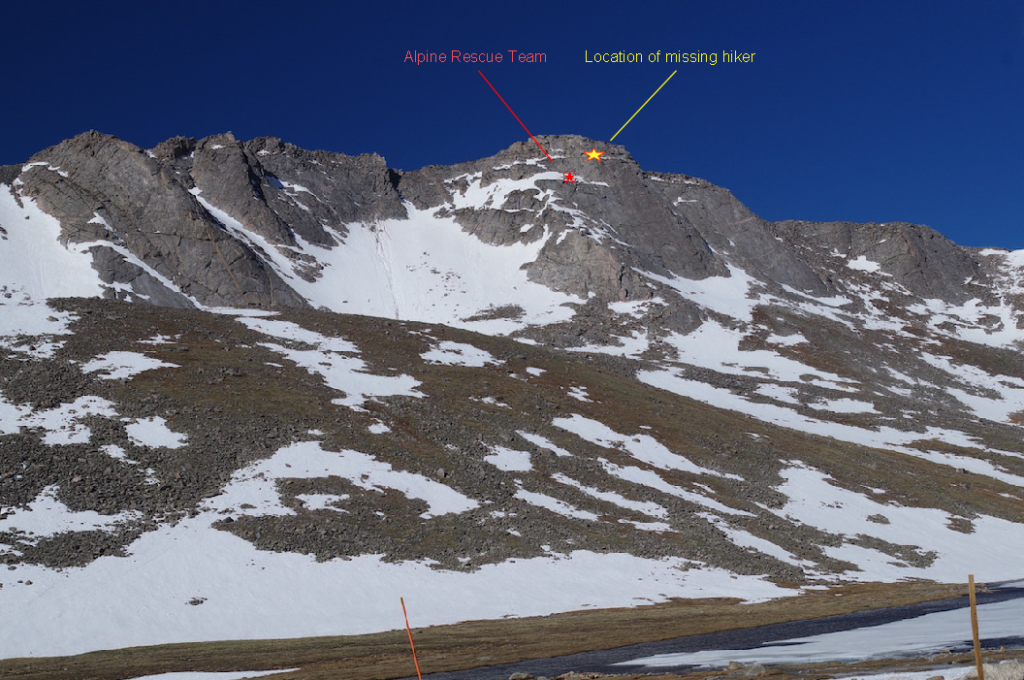

As the first gray light of dawn touched Summit Lake’s flat surface, ART and RMRG teams deployed along the West Ridge, and the Alpine team began by gingerly lowering a man from the tumbled ridge crest. In a stroke of good luck helped along careful spotting from Alpine members stationed at Summit Lake, he descending in direct line with the shivering hiker. In a stroke of bad, the rope he clung to came down five feet short of the mark.

“The rescuer had to rig personal webbing and cord to safely reach the young man,” Woody says. “But he got him.”

The rescuer immediately strapped the freezing boy into a harness and then plied him with food, water and warm clothing. While the Alpine team above hauled the pair 400 feet to the ridge, the Boulder crew did the same for Alpine’s exhausted Spalding team. By 9 o’clock, Woody’s hoped-for boring shift was pushing 24 hours of non-stop crises. But if ART has accomplished a lot of notable rescues, the Mount Evans mission stood out not only for its uncommon challenges and complexity, but for the real and significant risks it posed the rescuers. That everyone made it home intact is testament to the value of training, experience and iron nerve.

The rescuer immediately strapped the freezing boy into a harness and then plied him with food, water and warm clothing. While the Alpine team above hauled the pair 400 feet to the ridge, the Boulder crew did the same for Alpine’s exhausted Spalding team. By 9 o’clock, Woody’s hoped-for boring shift was pushing 24 hours of non-stop crises. But if ART has accomplished a lot of notable rescues, the Mount Evans mission stood out not only for its uncommon challenges and complexity, but for the real and significant risks it posed the rescuers. That everyone made it home intact is testament to the value of training, experience and iron nerve.

“We had 33 men and women on that mission, and we needed every one of them.”

Viewed in the warm light of day it was clear the boy had initially fallen a short distance from above, landing unharmed, but utterly trapped, on a ledge no bigger than the average coffee table perched above 1,000 gulp-inducing feet of certain death. And yet, with that unaccountable resilience of youth, the lad walked out under his own steam, climbed into his companion’s car and toodled back to Atlanta without a word about how he’d arrived at his terrible predicament. That’s okay though, because everybody at Alpine Rescue Team already knew his story by heart.

“He went up there with a plan, and he changed it,” explains Woody. “hen you’re hiking in the back country, you need to make a plan, make sure somebody knows the plan, and then stick to the plan.

“That kid’s story could have ended a lot of different ways. It was our job to make sure it ended with him alive.”